What is Justice? – BKY Style

On 10 November 2023, we held the first session of our secular occasional series, Tzedek and Contemporary Socio-Legal Issues, looking at Mishnah and Jewish tradition while learning about the reality and lived experience of individuals whose cases feed into legislative history. The series will examine the background context underpinning policy as encountered by legal practitioners and researchers working on the ground in the UK and internationally.

The next session in the series will be on housing, including ‘decent homes’ and the responsibilities of landlords; looking at the place of “home” in Jewish texts and history, alongside contemporary legal issues. We will be joined by Connor Johnston, a specialist housing barrister from Garden Court Chambers. The evening will end with sharing delicious vegetarian pizza. Everyone is welcome to join us from 18:30pm on Friday 26 January 2024 at the Montagu Centre.

To whet your appetite and bring you up to speed, we thought we would provide you with an overview of what we discussed in the first session, which focused on conceptions of Justice in Jewish texts & history and their relevance to law and policy today.

What is justice?

We began by collecting words we associate with Justice from everyone in the room and quickly saw just how broad and diverse the term is.

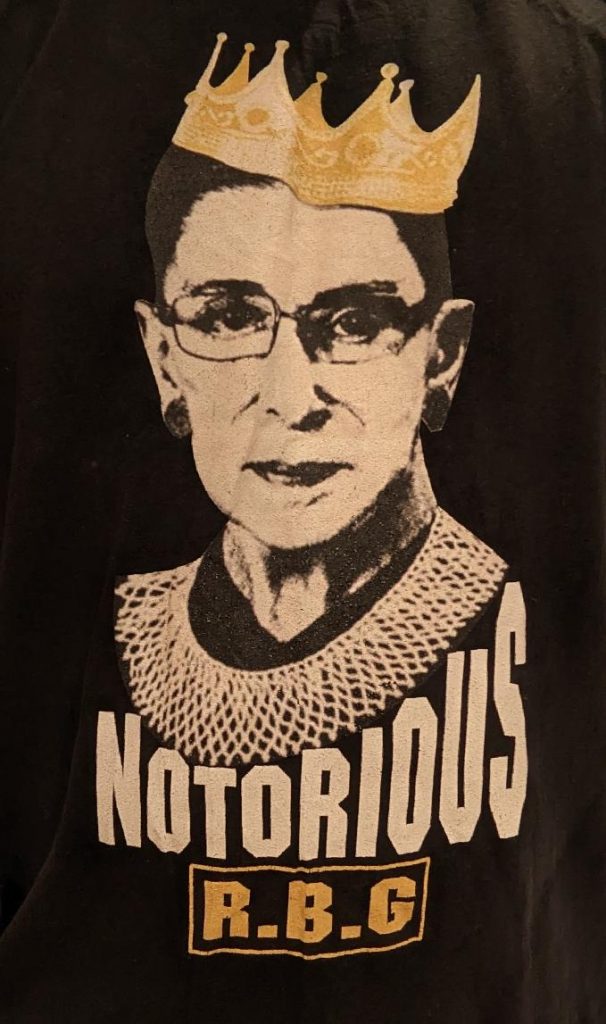

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (RBG) – work and legacy

We talked about Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg 1933-2020), (the first Jewish woman to reach the American Supreme Court), who famously had the words “Tzedek, tzedek tirdof,” or “Justice, justice you shall pursue” painted on the wall of her office.

Ginsberg’s tireless pursuit of justice was reflected in a stream of progressive decisions that changed and shaped the law in America, including critical work on gender discrimination and coercive sterilisation. We discussed some of her cases and how she also represented men in the pursuit of developing the law more widely on equality, to the great advantage of women generally as well as impacting broader human rights issues. Her famous, successful case, of Weinberger v Weisenfeld 420 U.S. 636 (1975) concerned a man who became a widower and could not access social security to support raising their child after he reduced his working hours to provide care for a newborn infant when his spouse died in childbirth: the Supreme Court ruled the gender based distinctions suffered by her client to be unconstitutional.

RBG, as Ginsberg was universally known, was a powerful advocate of women in law. Asked when would there be enough women in the Supreme Court, she replied “when there are nine” (the number of Supreme Court judges). She also famously said:

“I ask no favour for my sex, all I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our necks.”

Jewish justice – is there a place for human and moral rights?

Jewish conceptions and interpretations of Justice can be found around the world and throughout history.

Jewish lawyers were at the heart of developing international human rights law in the wake of the Shoah, for example the instrumentality of lawyers who were survivors, or who lost their family in death camps, to the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948; and their centrality to the establishment of the European Court of Human Rights in 1959. In recent months, as events have unfolded in Israel and Palestine, Jewish lawyers have sought to make sense of what justice requires.

Within weeks of the conflict beginning, Lord Neuberger and other prominent British Jewish human rights lawyers challenged the legal basis of Israel’s war: https://www.ft.com/content/9f1b190d-c955-4381-a6f5-ab4a2bf1c32c while David Pannick KC and others conversely argued for the right of Israel to use any means necessary to defend itself: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/times-letters-forging-a-path-towards-peace-in-middle-east-cbvwt2csk

There is a commonly held perception that the law consists purely of a hard and dispassionate set of rules and one which should not to be “abused” or used as a tool of social progress and change. This can be seen in the accusations of the tabloid papers of judges interfering in politics and in popular perceptions of the law and lawyers as self-serving and cynical.

Different times and cultures have seen the approach to the rule of law change drastically. Jewish lawyer Philippe Sands, describes these changes over time in his study of the West Africa legal case in a text entitled The Last Colony. That case concerned whether Ethiopia and Liberia could legally challenge South Africa’s discriminatory behaviour towards its colony. Sands writes:

“Remarkably, over the four years the case ran, [Judges] Spender and Fitzmaurice were able to revisit the earlier 1962 judgement – in which they had failed to persuade a majority to throw the case out – and procure a ruling that two African countries had no legal interest in challenging white South Africa’s racist and discriminatory actions against the Black inhabitants of its colony. Their thinking – that humanitarian considerations should be excluded from judicial process – now prevailed. The function of the Court was to apply legal rules, not moral precepts, Spender’s majority ruled, and those rules meant that one country could not bring a case to the Court to protect the rights of people in another country: the idea of an ‘actio popularis’ did not exist in international law. (Three years later, in another case, the Court reversed that ruling however, recognising that international law did recognise such a right, a decision that would pave the way, five decades later, for The Gambia to bring a case against Myanmar for alleged genocidal acts against the Rohingya community.)”

These two approaches to the law – adherence to rules versus natural or moral justice are also reflected in Jewish texts. Rabbi Janet Burden explained the term Chok (Chukim) which refer to law with no logical explanation – i.e. rules that must be obeyed as contrasting with the notion of Tzedek which refers to natural justice and Mishpatim which refer to laws that are grounded in moral reasoning.

Law and love

Jewish law can sometimes go even beyond moral reasoning. We discussed the well known order in Leviticus 19:18 – to “love your neighbour”.

Dr Laura Janes talked about how as a solicitor with experience of the law concerning social care, there is no legal compunction for the state or any public body to actually love someone. But Rabbi Janet Burden and others noted that the “love” of Leviticus 19:18 does not stand for any romanticised or idealistic notions of love. It is a construction of commitment, of a responsibility to life and to justice. And of course, that could be said to be found in modern day children’s law.

Law, sex and gender; disabilities and housing conditions

Professor Margaret Greenfields introduced some of the ways in which Jewish texts deal with sex and gender (including recognition of genders beyond male/female and the rights of inter-sex persons), a topic to which we will return, alongside other contemporary legal issues including war and the limits of behaviour, refugees and their treatment, disability issues (behaviour towards those who are experiencing intermittent mental health conditions or who have physical and sensory impairments) and quality of housing and the duties on householders pertaining to the conditions in which someone should or should not live.

We concluded the session by framing the discussion for the following event and inviting proposals for future sessions within the series to which guest speakers can be invited, or BKY members may wish to lead.